Shop Talk

Sheila Rants on Diagnosis

Before January break, Shop Talk covered the lever sign test to talk about sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios. We introduced the nomogram tool for estimating post-test probability of ACL injury. If you missed that issue or forgot about it in a fog of eggnog and Christmas cookies, you can find it here. Today we’ll look at the role of pre-test probability in diagnosis.

Before January break, Shop Talk covered the lever sign test to talk about sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios. We introduced the nomogram tool for estimating post-test probability of ACL injury. If you missed that issue or forgot about it in a fog of eggnog and Christmas cookies, you can find it here. Today we’ll look at the role of pre-test probability in diagnosis.

What is pre-test probability?

Pre-test probability is the chance that the patient has the condition, estimated before the test result is known. In the scenario from last December, we estimated - before we did the lever sign test - that our patient had a 75% chance of a torn ACL. 75% represented the pre-test probability of an ACL tear.

Our estimate was based on several factors like the prevalence of ACL injury in our setting (ski hill), the patient’s description of the incident (deep powder, twisted knee), and her symptoms (felt a pop, pain). With that history, our spidey senses started to tingle and we thought there was a good chance - 75% to be exact - that our patient had torn her ACL.

In her wonderful textbook on evidenced based physical therapy, Dianne Jewell talks about using gut instinct to estimate pre-test probability. Gut instinct, spidey senses, sixth sense. These are accurate descriptions of what it “feels like” when we make a prediction with limited information. I prefer to describe this phenomenon as tacit clinical insight. Our “gut” leads us to suspect an ACL injury because our anatomy class taught us the location of the ACL, kinesiology taught us that a twisting motion on a fixed foot is a good way to stress it, and our orthopedics courses taught us that a “pop” can signal a ligament rupture. It’s not an instinct; it’s our education speaking to us even when we don’t realize it. I urge you, “Don’t take for granted your tacit clinical insight! You were not born with it; you worked for it!”

How does pretest probability influence diagnosis?

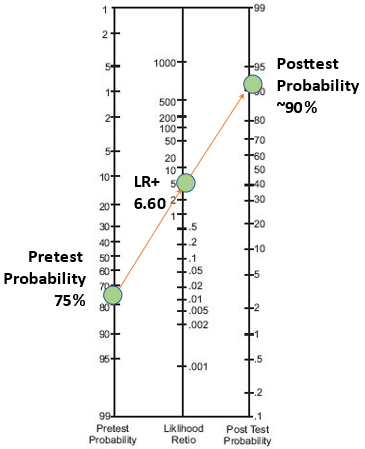

When we use a nomogram tool to rule-in or rule-out a condition, we place 1 dot on the pre-test probability and 1 dot on the likelihood ratio. Then we connect the dots to find the post-test probability. If it’s high, we rule-in the condition. If it’s low, we rule it out.

As illustrated in the images below, the location of the 1st dot influences the trajectory of the line. When our pre-test probability of ACL injury was 75% and the lever sign test was positive, the post-test probability of ACL tear was about 90%. We were pretty darn confident that our patient had torn her ACL.

But a positive test with low pre-test probability will not rule-in a condition. Let’s say our pre-test probability was only 10% and the lever sign test was positive. Now the post-test probability of an ACL tear is only about 40%. At 40%, we won’t rule it in. Instead, we might proceed with more testing because things aren’t quite adding up. It’s possible that the patient has an ACL tear, but her history is not typical. Or maybe the lever sign test provided a false positive.

One more thought…

It makes me a little crazy when critics argue that evidence-based practice does not value clinical expertise. Using a form of evidence, like a likelihood ratio, involves immense clinical skill. You’ve got to take a history and interpret it considering everything you know about what could be wrong with your patient. Then you must generate one or more possible diagnoses, tag a pre-test probability to each, select appropriate tests, and execute them skillfully. Those are all clinical skills. Without them, the likelihood ratio and nomogram are of little use. That’s why evidence-based decision making always relies on the best available external evidence and clinical expertise(1).

Thanks for reading and enduring my rant.

Footnote

(1) We often describe evidence-based practice as a 3-legged stool. Here we emphasize external evidence (leg 1) and clinical expertise (leg 2). The 3rd and equally important leg is the patient. Perhaps we’ll discuss the importance of the patient’s goals and expectations in another issue.

The Evidence Workshop, LLC

www.theevidenceworkshop.com

Demystifying research for better health care.

To comment or get more information, contact.

Sheila Schindler-Ivens, PT, PhD

Dept. of Physical Therapy, Marquette University

sheila.schindler-ivens@marquette.edu

Shop Talk is published periodically by The Evidence Workshop, LLC.

We are supported in part by Marquette University.

Copyright (2022) The Evidence Workshop, LLC. All rights reserved.

February Edition

Feb. 28, 2022

If you appreciate what we’re doing, please consider supporting our work. You can buy us a coffee or wish us happy birthday. February is our birthday month. Shop Talk is 2 years old!