Shop Talk

Diagnosing a Ski Injury

“The weather outside is frightful, but the fire is so delightful… Let it snow, let it snow, let it snow!”

“The weather outside is frightful, but the fire is so delightful… Let it snow, let it snow, let it snow!”

The folks at The Evidence Workshop are dreaming of a white Christmas. We don’t like to shovel, and we don’t like to shiver. But after Santa’s big ride, we’re heading up to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (UP) for some downhill skiing.

We’re not a skillful bunch, but skiing is an excuse to play in the snow and enjoy all 4 seasons the Midwest offers. After all, isn’t it the Swedes who say, “There’s no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing?” They are probably right when it comes to staying warm and dry, but good clothing won’t prevent a ski-related injury.

So, before we closed the Shop for our usual January break, we did some research on Alpine ski injuries and learned that knee injuries are among the most common. We also bumped into a new clinical exam, called the lever sign test, for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury. With any luck, we won’t need the test, and we hope you don’t, either. But here’s what we learned:

What is the lever sign test?

It’s a clinical test of ACL stability that is performed with the patient supine and the examiner’s closed fist under the proximal third of the calf. With the knee flexed slightly, the examiner’s other hand applies a downward force just proximal to the knee. If the ACL is intact, the heel will rise off the table, indicating a negative test. If the ACL has been disrupted, the patient’s heel will remain on the table, indicating a positive test.

Does the lever sign test have good face validity?

From the standpoint of mechanism-based reasoning, the test is sound. The developers argue that, when a fist is placed beneath the calf, the knee flexes approximately 30°. In this position, the origin and insertion of the ACL are maximally separated. The ligament is taut. Because the ACL’s job in life is to prevent posterior displacement of the femur with respect to the tibia, a downward force on the thigh will further increase tension on the ACL, causing the knee to extend and the foot to rise off the table. If the ACL is torn, there is nothing to counteract the posterior movement of the thigh. The foot stays put.

Did we need a new ACL test?

Maybe.

Developers argue that the lever sign test is easier than the tests we grew up with (i.e., anterior drawer, Lachman, pivot shift). The older tests require that we stabilize the thigh while manipulating the leg. During the lever sign test, the table supports the whole lower limb.

Does the lever sign test work?

Yes, but it's more trustworthy when you get a positive test result, as compared to a negative result.

A good diagnostic test will distinguish (with a high level of certainty) between people with and without a condition. A test’s ability to do so is measured in several ways, including sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratio. A recent systematic review with meta-analysis by Abruscado et al. provides the following pooled values for the lever sign test:

Sensitivity 0.77

Specificity 0.90

LR+ 6.60

LR- 0.22

Large values for sensitivity and specificity are good. The closer to 1, the better. So, the lever sign test is quite specific, but not as sensitive. Let’s see what that means.

A perfectly specific test is one that detects all true negatives. It’s most valuable when it’s positive. I know that’s counterintuitive, but let’s think about it this way. A specific test is so darn good at detecting true negatives, it will never miss one. So, when the specific test is positive, you can be sure the patient has the condition. You may have seen this concept summarized in the mnemonic device, SpPin, which reminds us that when a Specific test is Positive, you can rule-in the condition.

A perfectly sensitive test is one that detects all true positives. It’s most valuable when it’s negative. Here we go again. A sensitive test is so good at detecting true positives, it will never miss one. So, when it’s negative, you can be sure your patient is free from the condition. Here, we use SnNout to remind us that when a Sensitive test is Negative, you can rule-out the condition.

In summary, the lever sign test is really trustworthy when it provides a positive test, but less so when it gives a negative test.

The same conclusions are evident in LR+ and LR-. These abbreviations stand for positive(+) and negative(-) likelihood ratio (LR). If you are an old-timer, you probably did not learn LR+ and LR- in school. But these concepts are standard fare in evidence-based practice courses these days. While you track down a colleague under 40 to explain it, let this explanation suffice.

A good diagnostic test should have a high LR+ and a low LR-. Think, plus(+) high, minus(-) low.

LR+ represents the likelihood of a getting a positive test in someone with the condition as compared to someone without it. In theory, we want LR+ to be infinitely large, meaning the test is positive only in those who have the condition.

LR- is the likelihood of a positive test in someone without the condition as compared to someone with it. In theory, we want LR- to be zero, meaning that the test is never positive in people without the condition.

Some sources suggest that a good diagnostic test should have LR+ >10 and/or LR- <0.10. But, in our experience, many clinical tests in PT don’t score that well. So, 6.60 an 0.22 are not too shabby.

How can this information help diagnose ACL injury?

Consider this scenario:

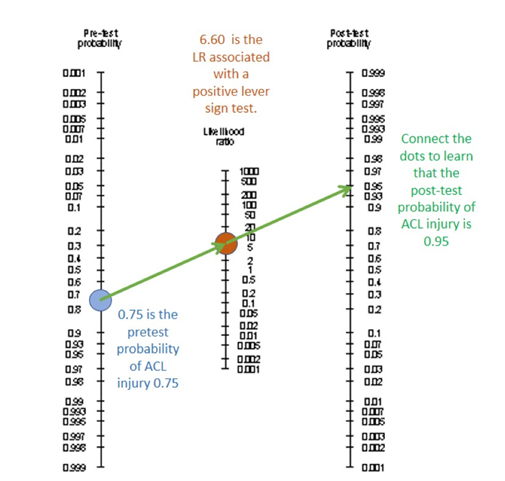

A patient walks into your clinic with loaner crutches from the nearby ski lodge. She reports knee pain and some swelling. She tells you she was skiing with her family, caught her tip in some deep powder, twisted, and felt a pop. You suspect an ACL tear. Given the incidence of ACL tears near the ski hill and your knowledge of the incident, you estimate that she has a 75% chance of a torn ACL. You do the lever sign test and get a positive result. You pull out your handy nomogram tool for diagnostic testing and put a dot on the left-hand side at 0.75. Then you put a dot in the middle at 6.60. Finally, you connect the dots and extend the line to the right-hand side. You read a value of 0.95, which means that there is a 95% chance that her ACL is torn. You deliver the bad news.

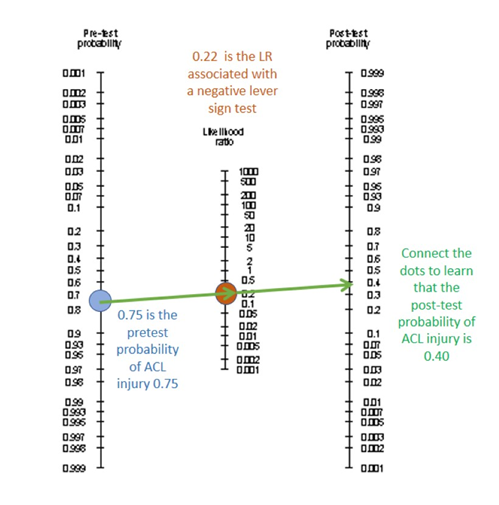

Had your patient tested negative on the lever sign test, you would have placed the middle dot on 0.22, connected the dots, and learned that the post-test chance of ACL tear is 40%. That’s a disappointing answer. Not because her ACL might be OK, but because you’re not sure; 40% is a somewhat equivocal conclusion. A negative result on a test with a very small LR- will push you toward 0% chance of injury, just like the LR+ above pushed you to near certainty of injury. Again, the lever sign test is a little better at ruling-in ACL injury than it is at ruling it out.

Thanks for reading. Very best wishes for a relaxing holiday break, and Merry Christmas to those who are celebrating. We’ll see you in February when Shop Talk returns. As always, you can find additional resources at the end of this post.

Want to learn more?

1. This is systematic review we pulled our values from. It’s free on PubMed Central. Several of the author were student PTs. Kudos to them for publishing early in their career and to their mentors at Walsh University who helped make it happen.

· DIAGNOSTIC ACCURACY OF THE LEVER SIGN IN DETECTING ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT TEARS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS. Abruscato K, Browning K, Deleandro D, Menard Q, Wilhelm M, Hassen A.Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2019 Feb;14(1):2-13. PMID: 30746288 Free PMC article

2. This is a terrific (and free) paper explaining sensitivity, specificity, LR+, and LR-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4975285/

3. Here’s a few more papers examining the lever sign test. Some are free; some are not. One is in German.

· Implementing the Lever Sign in the Emergency Department: Does it Assist in Acute Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture Diagnosis? A Pilot Study. McQuivey KS, Christopher ZK, Chung AS, Makovicka J, Guettler J, Levasseur K. J Emerg Med. 2019 Dec;57(6):805-811. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.09.003. Epub 2019 Nov 7. PMID: 31708315

· Diagnostic Accuracy of Lever Sign Test in Acute, Chronic, and Postreconstructive ACL Injuries. Gürpınar T, Polat B, Polat AE, Çarkçı E, Öztürkmen Y. Biomed Res Int. 2019 Jun 9;2019:3639693. doi: 10.1155/2019/3639693. eCollection 2019. PMID: 31281835 Free PMC article.

· Critical Analysis of the Lever Test for Diagnosis of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Insufficiency. Massey PA, Harris JD, Winston LA, Lintner DM, Delgado DA, McCulloch PC. Arthroscopy. 2017 Aug;33(8):1560-1566. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.03.007. Epub 2017 May 9.PMID: 28499922

· The "Lever Sign": a new clinical test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Lelli A, Di Turi RP, Spenciner DB, Dòmini M. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016 Sep;24(9):2794-2797. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3490-7. Epub 2014 Dec 25. PMID: 25536951 Clinical Trial.

· Lever-Sign-Test - Einsatzbereit. [No authors listed] Sportverletz Sportschaden. 2016 Jun;30(2):82-3. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1583255. Epub 2016 Jun 14. PMID: 27299962 German. No abstract available.

4. This article suggests that knee injuries are common in downhill skiing. It’s out of Canada, and Canada knows winter sports.

· Injury trends in alpine skiing and a snowboarding over the decade 2008-09 to 2017-18. Dickson TJ, Terwiel FA. J Sci Med Sport. 2021 Oct;24(10):1055-1060. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2020.12.001. Epub 2020 Dec 11. PMID: 33384220.

5. For more on mechanism-based reasoning, check out our archive.

https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ptworkshop/hydroxychloroquine-covid-19

6. This Wikipedia post describes Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_Peninsula_of_Michigan

Christmas Edition

Dec. 23, 2021

If you appreciate what we’re doing, please consider supporting our work -